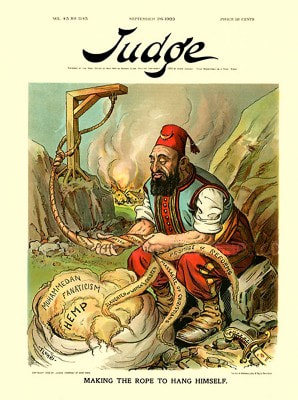

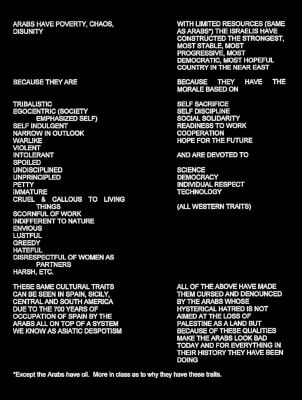

AuthorBy Alex Barna, The University of Chicago Teaching about the Middle East, Arabs, Muslims, or Islam in a contemporary high school or college classroom presents certain pedagogical challenges. The following is an excerpt from a teaching module titled “The Middle East as Seen Through Foreign Eyes” composed and edited by John Woods, Professor of Central Asian and Iranian History at the University of Chicago, and Alexander Barna, Outreach Coordinator at the University of Chicago’s Center for Middle Eastern Studies. This teaching module is part of the Oriental Institute’s “Teaching the Middle East: A Resource for High School Educators” project and was funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. To read the rest of this module and others, please visit: http://teachmiddleeast.lib.uchicago.edu/index.html. Teaching about the Middle East, Arabs, Muslims, or Islam in a contemporary high school or college classroom presents certain pedagogical challenges. Rather than accepting and internalizing new information imparted to them about the culture and history of this region of southwestern Asia, it is apparent that negative perceptions, attitudes, and stereotypes can condition students to reject or deny the validity of truth-claims incongruent with their own. As Walter Lippmann keenly observed in Public Opinion (1922), “The only feeling that anyone can have about an event he does not experience is the feeling aroused by his mental image of that event.” Thus, in the context of education it is imperative of teachers to determine what their students think they know in order to understand their beliefs and build a basis for mutual understanding. To understand the term “stereotype” in its current usage, it is instructive to turn again to Lippmann. He defined “stereotype” as a “distorted picture or image in a person’s mind, not based on personal experience, but derived culturally.” Lippmann reasoned that the formation of stereotypes is driven by social, political, and economic motivations, and as they are passed from one generation to the next, they can become quite pervasive and resistant to change. Historically, state actors have mobilized stereotypes in service of the social process that Lippmann calls “the manufacture of consent.” For instance, in times of war or economic hardship, governments and political parties have used stereotypes to reconfigure ethical landscapes and delineate new boundaries separating protagonists (the “in-group”) from antagonists (the “out-group” or “enemy”). Taken to a logical extreme, this sort of us-versus-them polarization ultimately enables members of the in-group to tolerate or even rationalize harming members of the perceived out-group. Two other uses of stereotypes are worth noting, one psychological and the other epistemological. The psychological construction of a polar-opposite foil provides a scapegoat onto which members of an in-group project or transfer the qualities within their society they find unacceptable or intolerable. This mental endeavor has an epistemological payoff. By creating a foil and ascribing to it a set of determinable characteristics, a member of the in-group acquires “knowledge” of the out-group, which aids him or her in reducing a menacing, unpredictable, and unknown entity down to a more simple, predictable, and knowable adversary. Lippmann provides a helpful description of all three uses of stereotypes in the following passage: “The system of stereotypes may be the core of our personal tradition, the defenses of our position in society. They may not be a complete picture of the world, but they are a picture of a possible world to which are adapted. In that world people and things have their well-known places, and do certain expected things. We feel at home there. No wonder, then, that any disturbance of the stereotypes seems like an attack upon the foundations of the universe. [The pattern of stereotypes] is the projection upon the world of our own sense of our own value, our own position, and our own rights. The stereotypes are, therefore, highly charged with the feelings that are attached to them. They are the fortress of our tradition, and behind its defense we can continue to feel ourselves safe in positions we occupy.” Rooted in ignorance, misconceptions, and negative images and attitudes, the stereotype provides a distorted mental picture or set of images that develop through reductionism into prejudice, bias, and eventually racism. Two powerful, related rhetorical tropes, synecdoche and metonymy, are involved in this process. Synecdoche is a figure of speech where a part of something is taken to represent the whole, the specific to represent the general or vice versa. Examples include hand for sailor, law for policeman, and steel for sword. Metonymy involves a substitution, where a concept is replaced by something to which it is closely related. Examples of metonymy include the use of the word Washington to mean the federal government of the United States. Both of these terms are at work in the fabrication of stereotypes of the Middle East, Islam, and Muslims. For instance, any individual Muslim can stand in and speak for all Muslims everywhere. Muslim and Arab are often collapsed into a single identity, suggesting that all Muslims are somehow Arab and vice versa. Similarly, the government of a Muslim majority nation-state is indistinguishable from governments of other Muslim majority nation-states. Material objects associated with the Middle East – camels, palm tree oases, robes, tents, and sand – denote metonymically the entirety of Arabo-Islamic religion and civilization. Saddam Hussein represents all Iraqis, and Ayatollah Khomeini or Mahmud Ahmadinejad all Iranians. Finally, Islamic religion and culture are seen as monolithic, never differentiating between religious and secular, between sacred and profane.  MAKING THE ROPE TO HANG HIMSELF, 1903. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Ottoman Empire was politically and economically unstable. Over the course of the nineteenth century, the Ottomans had lost a considerable amount of their territory to expanding European powers, and they were heavily indebted to European banks. As result of its economic and financial distress, Western political leadership began to refer to the Ottoman Empire as a perilously “sick man.” In 1903, cartoonist Emil Flohri drew a cover for Judge, an American political satire and humor magazine, which reflected this sentiment by showing the Ottoman Turk making the preparations for his own execution. Rather than attributing the weakening of the Ottoman Empire to financial and economic problems caused by foreign interference, Flohri censures the Ottomans themselves. Their collective demise is an effect of cultural character, and inscribed on the noose the Turk crafts for himself are the symptoms of his downfall: “Mohammedan fanaticism,” “slaughter of women and children,” “massacre of Christians,” and an insincere promise to enact reforms. Flohri’s satirical braiding of Islamic fanaticism with misogyny and violent intolerance of Christians in the context of a faltering Ottoman Empire is over one hundred years old, and his commentary is more evidence of the historical durability of negative stereotyping once a certain mental image has taken hold. Dating back to the beginning of the Cold War, several factors – including but not limited to 1) competition over Middle East oil; 2) the shortcomings of US foreign policy; 3) extremist religious ideologies; 4) the supposed “encroachment” of American Muslim communities in both urban and suburban settings; and 5) resentment toward “immigrants” during times of economic uncertainty and high unemployment – are mutually reinforcing in creating a negative social atmosphere vis-à-vis Islam, Muslims, and the Middle East. Elements of this negative social atmosphere range from loss of civility through prejudice and racism to the proliferation of hate crimes against minority ethnic, religious, and cultural groups. It appears that alongside those threatening us from abroad, we have discovered a number of enemy “Others” within. In his exploration of the psychology of homo hostilis, Sam Keen observes, “In the beginning we create the enemy. Before the weapon comes the image.” He continues, “We think the Other to death and then invent the battle-axe or the ballistic missiles with which to actually kill them. Propaganda precedes technology.” In other words, the construction of an enemy comes from within the human psyche and violence against a perceived enemy is predicated on an understanding of what that enemy constitutes or represents. Despite changing contexts and circumstances, Keen claims that a society or people have “a certain standard repertoire of images it uses to dehumanize the enemy. In matters of propaganda, we are all Platonists; we apply eternal archetypes to changing events.” If we accept Keen’s thesis, then images and stereotypes of the Islamic world are not only historically broad, but psychologically deep as well. Through survey and analysis of written and visual materials related to many different conflicts and many different peoples, Keen constructed a universal typology of enemy-making consisting of several tropes and archetypes, which range from the enemy as an uncivilized and violent brute force to the enemy as insects or vermin. The application of Keen’s categories to materials pertaining to the Middle East and wider Islamic world reveals that American notions of a Middle Eastern or Muslim Other follow a pre-existent and predictable pattern of vilification. It is clear that American popular imagination has, to a certain degree, been conditioned to view Muslims as “the enemy” and Islam as the political and moral equivalent of communism and European fascism. It is further apparent that this material and the perceptions it engenders are encountered in every segment of American culture: the press, journals of opinion, literature, electronic news and entertainment media, religious institutions, government, and education. Through recent developments in telecommunications – the internet, 24-hour news channels – and through the fear and insecurity instilled by the terrorist attacks of September 11, new venues and new motivations have emerged for propagating negative stereotypes of Islam and the Middle East. However, material now accessible on the World Wide Web or beamed in by satellite has remained consistent with the words and images disseminated prior to the appearance of these new technologies. On the Internet and in the 24-hour news cycle, Keen’s typology remains valid.  MIDDLE SCHOOL SOCIAL STUDIES HANDOUT. NORTH CHICAGO SUBURBS, 1987. During the 1980s a middle-school social studies teacher distributed the handout below to his students. On a single page the handout presents a series of black-white binary oppositions which serve to explain why the Arab world is afflicted with “chaos and disunity” as compared to the modern West. The content is familiar. Not only is it an abbreviated index of the recurring stereotypes that Europeans and Americans have attributed to a Middle Eastern people for centuries, but it is also reminiscent of a program of demonization directed at any group perceived to be an enemy other. The context in which it was disseminated, a middle-school classroom in the suburban Midwest, shows how widespread the process of enemy-making vis-à-vis the Middle East had become in the late twentieth century.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

What We Do |

Middle East Book Award |

© COPYRIGHT 2018. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed